“Making the impossible possible.”

The phrase describes Kimberly Bennett’s research into treating children’s brain tumors – and her journey from outsider to leader, from the desert of Hesperia to the halls of Harvard-MIT.

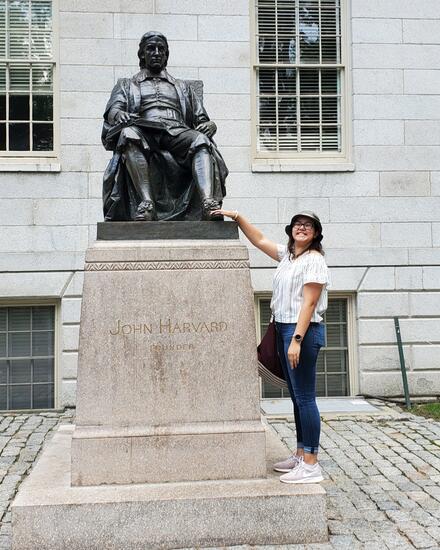

Bennett, a 2021 graduate of the UC Riverside Harlan and Rosemary Bourns College of Engineering, heard from peers that she would be rejected by Harvard-MIT’s Health Science and Technology program. “It’s too competitive,” they said. “It’s too hard to get in from Riverside.”

Today, not only is Bennett in, but this year she received three awards to support her graduate work there: fellowships from the Ford Foundation, the National Science Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. All three confer merit-based grants to facilitate advanced academic research.

“Shock, pride, disbelief, grateful,” Bennett said. “These words cannot fully describe how I feel receiving these awards as someone from a first-generation background who didn't understand what research and graduate school were until later in my academic career.”

Today, Bennett assists with research almost as complex as the brain itself; it centers on finding treatments for pediatric brain tumors called diffuse midline gliomas. The gliomas, which strike children ages 2 to 7, resist standard chemotherapy and are always fatal, she said, usually within a year of diagnosis.

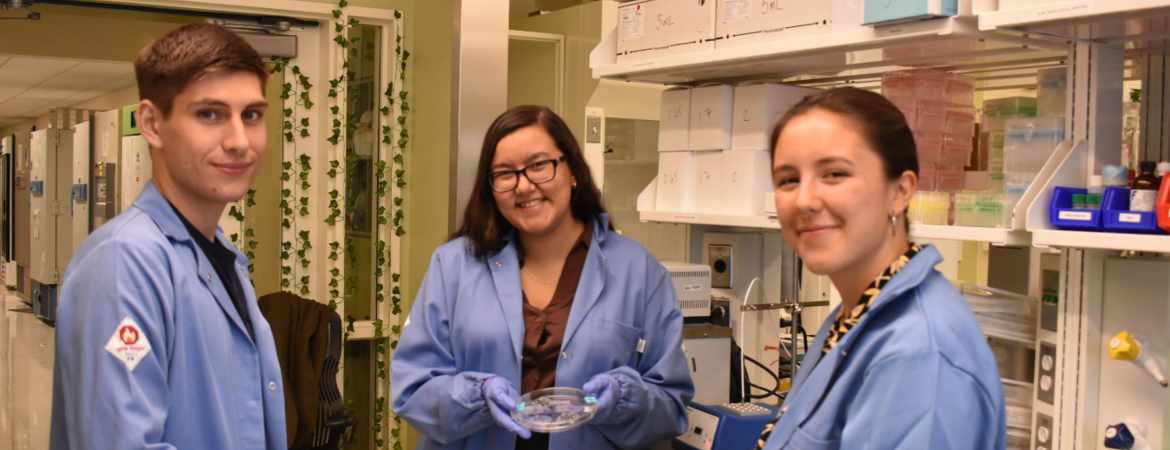

Bennett’s work at MIT includes recreating human organ systems on a microscale and building and testing “gobstopper” drugs that use layers – and combinations of layers – of nanoparticles to deliver chemo drugs directly to the gliomas.

“It’s about making the impossible possible,” Bennett said. “I can’t wait for the future, when a parent doesn’t have to lose a child in such a devastating way.”

Bennett, a first-generation Mexican-American, grew up in rural Southern California, without affluence or access to advanced coursework, science camps or college-preparatory resources.

Her mother, a nurse’s assistant, and her father, previously a maintenance mechanic, encouraged her education; when she enrolled at UCR, Bennett – drawn to math, science, writing and history but unsure of much beyond that – became the first in her family to attend college.

While she enjoyed the challenge, she felt alone, different, unprepared compared with her peers in Bourns’ bioengineering program. “For all these people, this class is so easy,” she recalls thinking. “They have done this since they were 5 … (but) I had to figure out everything. It can feel isolating if you feel like you’re the only one struggling.”

She flourished, she said, thanks to UCR professors Victor Rodgers and Byron Ford, who listened, offered counsel, and praised her curiosity and willingness to learn. Bennett related to their journey as minority scientists: “They had my best interests at heart and really cared.”

The two mentors also inspired Bennett to pursue the rigorous dual path of medical engineering and medical physics in graduate school. She liked the challenge – “kind of like learning two languages” – along with the human good she could do by applying engineering to medicine.

Examples of the engineering/medicine combination include designing prosthetics, gene editing to correct disease-causing mutations, and, as in Bennett’s case, creating targeted drug delivery strategies for chemotherapy. “It’s anything where engineering and medicine combine to give people a better life,” Bennett said.

She has also improved life for other students who have felt alone, disconnected or less experienced than others in academic settings. She is the co-founder of GFLI@MIT, a group for graduate students from first-generation and/or low-income backgrounds at MIT.

“The goal is to make a first-gen family,” Bennett said. “We’re building a community here for a population that can feel ignored or invisible” – and often had less opportunity growing up.

Bennett’s career goals include staying in academia to continue both her research in pediatric neuro-oncology and her first-generation leadership: “There are not many professors or Ph.D.s with my background. I want to help change the narrative, show what we can do – enter spaces and show up.”

Outside of science and medicine, Bennett enjoys snapping photos, filling scrapbooks and creating outdoor adventures: hiking trails, camping and traveling.

Asked about the lessons learned on her journey, she said, “Don’t dwell on comparisons to others who may have started with more help and resources. See your differences as a strength. … At the end of the day, I’m still here.”

Connect with Kimberly Bennett at https://www.linkedin.com/in/k-bennett/