How can machine learning preserve, protect, and restore the human brain?

That’s a question for the Laksari Lab at the Marlan and Rosemary Bourns College of Engineering (BCOE), where engineers help improve outcomes for stroke patients, athletes who suffer concussions, and people subject to frailty or a state of physical decline due to aging.

“I believe in the impact of academic research in improving human lives,” said Kaveh Laksari, assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering.

In this case, that means applying engineering concepts — via research ideas — to medicine.

“In a clinic, you can easily see how modern imaging technology, biomedical devices, and fast computation and AI … improve diagnostics and care,” he said.

As Laksari continues his research on stroke diagnostics, he gets closer to the ultimate goal: improving human health.

Consider: As a stroke goes untreated, the average patient loses 1.9 million brain cells per minute — perhaps leading to death or the impairment of speech, mobility, memory, or vision.

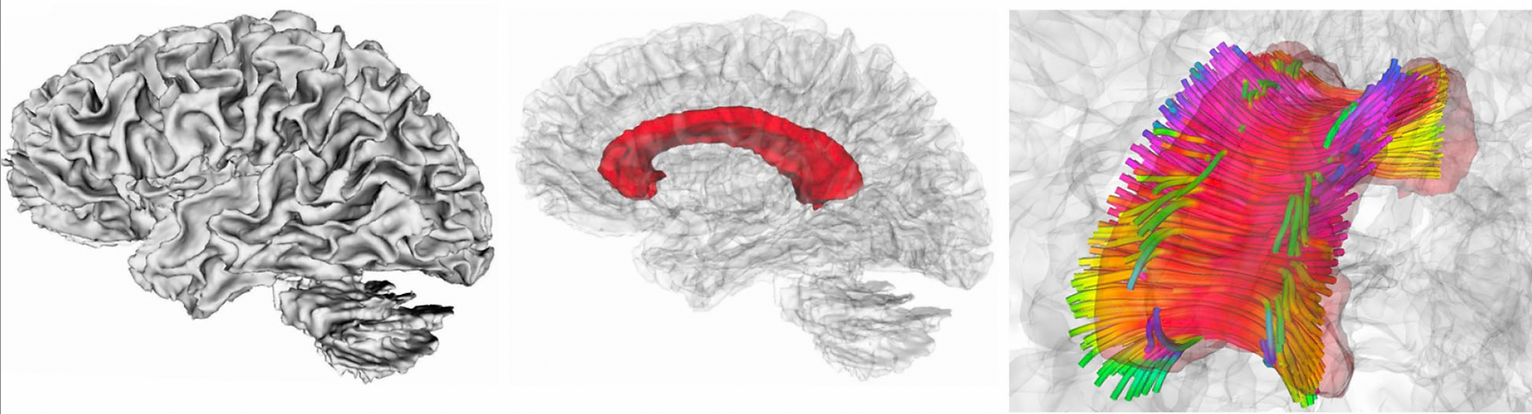

To help avoid such severe outcomes, Laksari has pioneered technology using a computer tomography (CT) scan — a diagnostic imaging technique — to model stroke damage and determine whether a patient needs surgery to relieve blood clots blocking oxygen to the brain.

Laksari’s modeling is safer, faster, and more accessible than a standard brain test that utilizes tiny radioactive particles, or a perfusion scan: It cuts radiation exposure, takes just seconds to complete, and requires no expertise to read.

Laksari, who joined BCOE in 2023 after six years at the University of Arizona, calls himself an avid sports fan: He played college soccer (as a midfielder) and closely follows the NBA (his team: the Golden State Warriors). He lived in Tehran until age 27 — the product of an engineer father and a chemist mother. His mother pushed him in school, he said, while his father provided encouragement.

As a child, Laksari thought he’d perhaps become a doctor. But after studying engineering as an undergraduate in Iran, as a graduate student at Temple University, and as a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University, he’d found his niche: applying mechanical engineering principles to the body and brain to produce better health outcomes.

“Once you get a sense of what engineering has to offer,” Laksari said, “it is very hard to look away.”

At Stanford, Laksari began assessing concussion detection and prevention in athletes such as mixed martial arts (MMA) fighters and football players, a research area he later brought into his lab.

Thanks mostly to mouth guard sensors, Laksari’s technology can track athletes’ speed and movement and correlate collision data with metrics that can signal a head injury. These metrics can include brain oxygen levels and blood biomarkers, which are measurable processes, molecules, or proteins that indicate a state of health.

With this information available in real-time, coaches and others can better determine if a player should visit the hospital — or stay on the sideline to avoid a more-serious secondary concussion. The research also helps experts enhance the design of helmets and other protective gear.

Likewise, Laksari’s frailty-assessment research relies on wearable sensors such as smartwatches to collect data such as step count, speed, and consistency. It then applies machine learning to correlate that information with frailty metrics and assess whether each patient is healthy, pre-frail, or frail. The result: straightforward health data that helps patients and their doctors decide on interventions that can boost conditioning, reverse damage, and delay further decline.

The drive for tangible ways to help people is a theme in Laksari’s work.

When asked what in his career he’s most proud of, he said, “As an academic, of course, the research is significant, but I’d also have to say training and mentorship are as important.”

He expressed pride in developing student scholars and in their many contributions to engineering, both in his lab and later in their careers.

“This is very high-level and difficult research,” Laksari said. “And it’s the students who do the work. I’m the manager working with them. They should get the credit, and I’m proud of that.”

He currently has three graduate students and one post-doctoral researcher. His advice for them?

“Perseverance is key. Often, the experiments don’t work as you expect them to, or the results don’t satisfy your hypothesis, and so on,” he said. “But you need to be able to keep pushing ahead. … I always say, ‘If this were easy, someone would have done it by now.’”

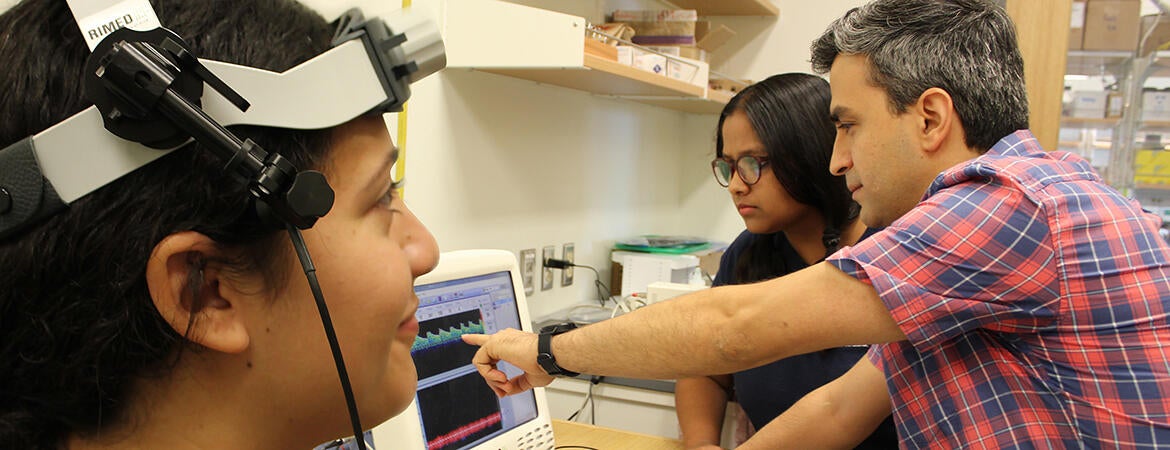

Header image: Kaveh Laksari with students in his lab (Photo courtesy of Kaveh Laksari).